5 greenwashing lies about waste management

These days, many companies and brands are promoting their sustainability and eco-friendly initiatives. At first glance, this seems promising: “The world is finally recognizing the importance of our environment,” we might say. However, behind those green promises and sustainability claims, the reality is often far worse. Consumers are drawn to green advertisements and believe in them, feeling good about supporting what they think are ethical companies. Unfortunately, these businesses often use the profits from this support to mask their true intentions, navigating through laws and regulations without making meaningful changes. In this blog, we will reveal five greenwashing lies specifically related to waste management and discuss their impact on the environment and economy.

Lie number 1: “Fashion brands’ own take-back schemes for textile waste are well-functioning systems.”

Claim: Take-back schemes offered by fast-fashion brands are marketed as a convenient and responsible option for consumers to return unwanted clothing. Brands promise that these garments will be donated, recycled, or given a second life.

Reality: While these initiatives are promoted as sustainable, only a small portion of collected garments are recycled or reused. Most are downcycled, destroyed, or sent to countries without proper waste management, worsening environmental damage.

The problem with take-back systems by fashion brands is well-discussed in the report by Changing Markets Foundation, “Take-Back Trickery.” They tracked the path of 21 clothing items deposited in take-back schemes from major brands like H&M, Zara, C&A, Primark, Nike, Boohoo, New Look, The North Face, Uniqlo, and M&S using concealed trackers. The investigation, conducted between August 2022 and July 2023, categorized results based on the final destination of the clothes:

- Downcycled or Destroyed: 7 items were shredded, burnt for fuel, or became lower-value products like insulation materials.

- Resold within Europe: 5 items were resold, but the reselling process was inefficient, with significant travel involved.

- Lost in Limbo: 5 items were stuck in warehouses or never left the drop-off point.

- Shipped to Africa: 4 items were sent to Africa, contributing to local waste problems.

Luckily for European Union countries 2025 law mandating separate textile waste collection is being implemented to tackle the growing environmental challenges posed by textile waste. The law requires all EU member states to implement systems that ensure textiles are collected separately from other waste, preventing them from being disposed of in landfills or incinerated. This will encourage reuse and recycling, pushing the textile industry to develop new technologies for processing used materials. It also aims to reduce the overproduction of textiles by promoting a market for second-hand clothing and sustainable fashion. This law is part of the broader EU Circular Economy Action Plan, which seeks to make industries more sustainable and reduce overall waste.

With the help of Sensoneo, take-back systems don’t have to be that complicated. They just need to be implemented effectively. One of the best examples is the take-back system implemented for ASEKOL, a nationwide collector of WEEE in Czechia, which helps to maximize efficiency with accurate real-time data.

Lie number 2: “All products marked as biodegradable or compostable are environmentally friendly.”

Claim: Companies advertise their products or packaging as “biodegradable” or “compostable” to suggest they are environmentally friendly.

Reality: Many of these products only biodegrade under specific industrial conditions, which are not available in typical landfill or home composting scenarios. Without proper facilities, these items might persist in the environment just like traditional plastics.

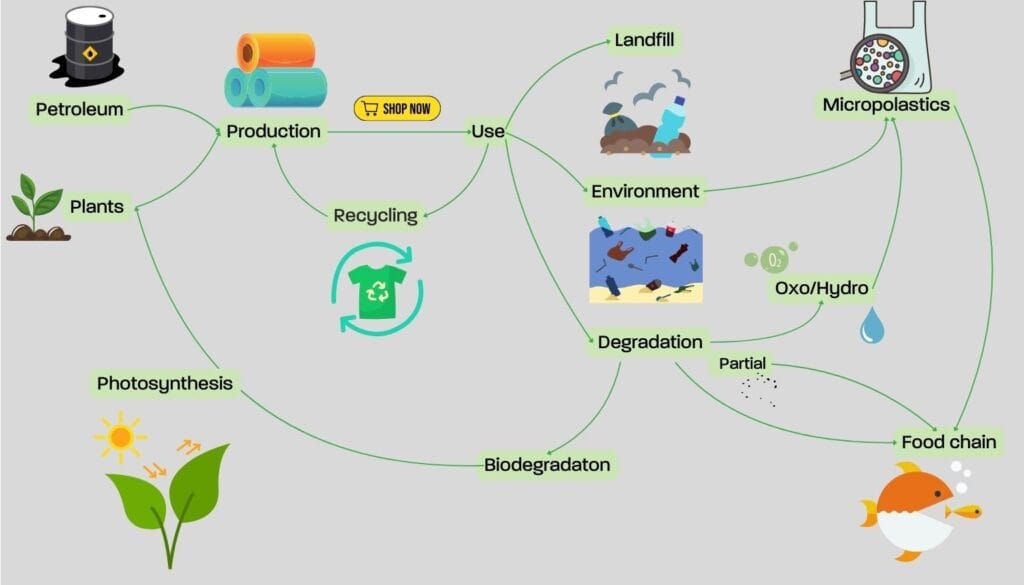

Overall, biodegradable plastics can be classified into two main categories based on their degradation mechanisms: oxo-biodegradable and hydro-biodegradable plastics.

Oxo-biodegradable Plastics:

Oxo-biodegradable plastics are made from petroleum-based polymers mixed with additives like metal salts to speed up their breakdown when exposed to oxygen. Their primary material source is naphtha, a byproduct of oil or natural gas. The main issue with oxo-biodegradable plastics is that they tend to break down into microplastics—tiny particles that can be ingested by wildlife and eventually enter the food chain. Though they degrade faster than traditional plastics, they are not recyclable and typically end up in landfills. In landfill environments, especially in deeper layers where oxygen is limited, their degradation slows down or stops completely. These plastics also require UV light to activate degradation, but landfills, buried under soil and debris, often lack sufficient sunlight, further hindering the degradation process. Moreover, the breakdown of oxo-biodegradable plastics releases greenhouse gases like CO₂ and methane, along with toxic chemicals that can harm both the environment and living organisms, including humans.

Hydro-biodegradable Plastics:

Hydro-biodegradable plastics break down quickly through hydrolysis and include materials like polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA) and polylactic acid (PLA). PHA is typically made from sugars from algae, while PLA comes from sugars in crops like corn and sugarcane. Hydro-biodegradable plastics face similar challenges when disposed of in landfills, where oxygen and moisture are scarce, leading them to persist for centuries while slowly releasing methane. In the natural environment, they can pose the same risks as traditional plastics like PET. Though these plastics have the potential to reintegrate into the ecosystem more quickly, this process only occurs in high-temperature industrial composting facilities, which are rare, particularly in developing countries where plastic pollution is a significant issue.

Lie number 3: “Companies regulate and recycle their waste.”

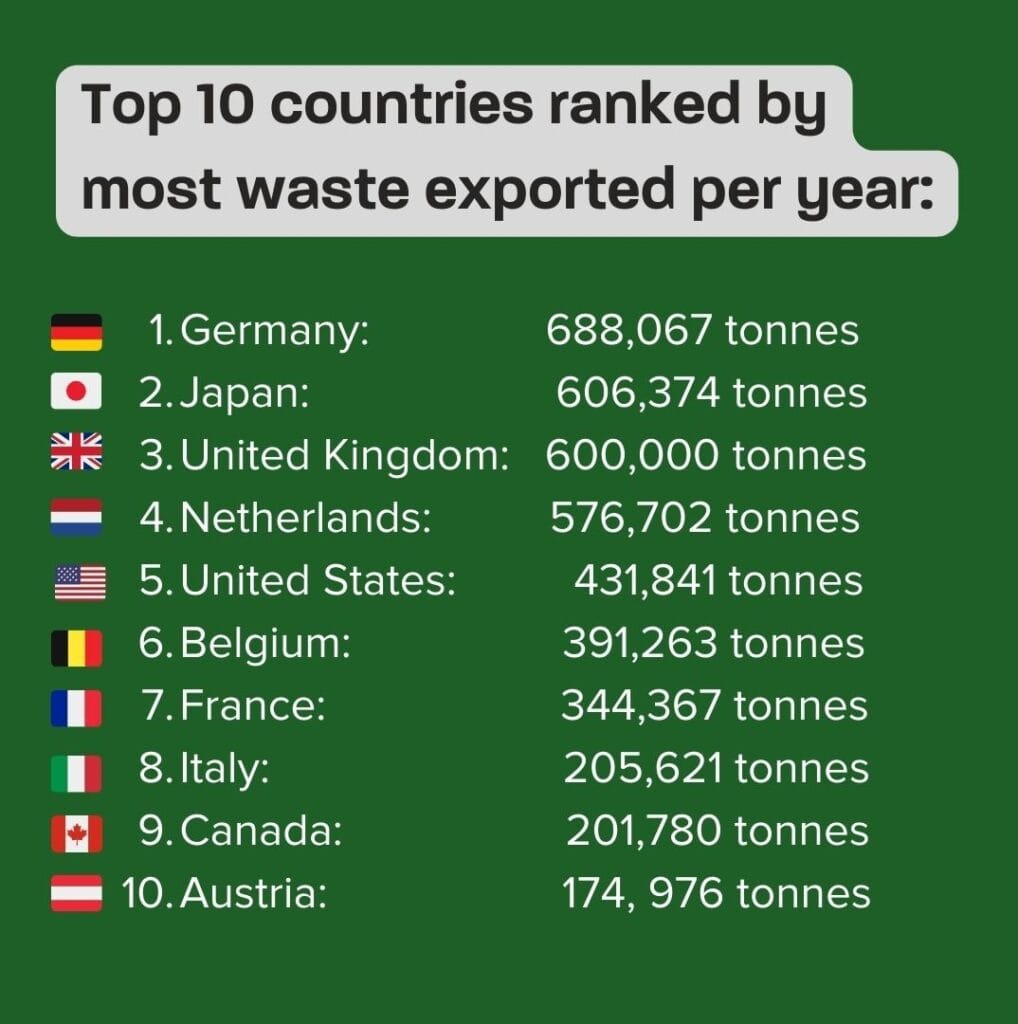

Claim: Companies claim that they are recycling waste by shipping it to other countries for processing.

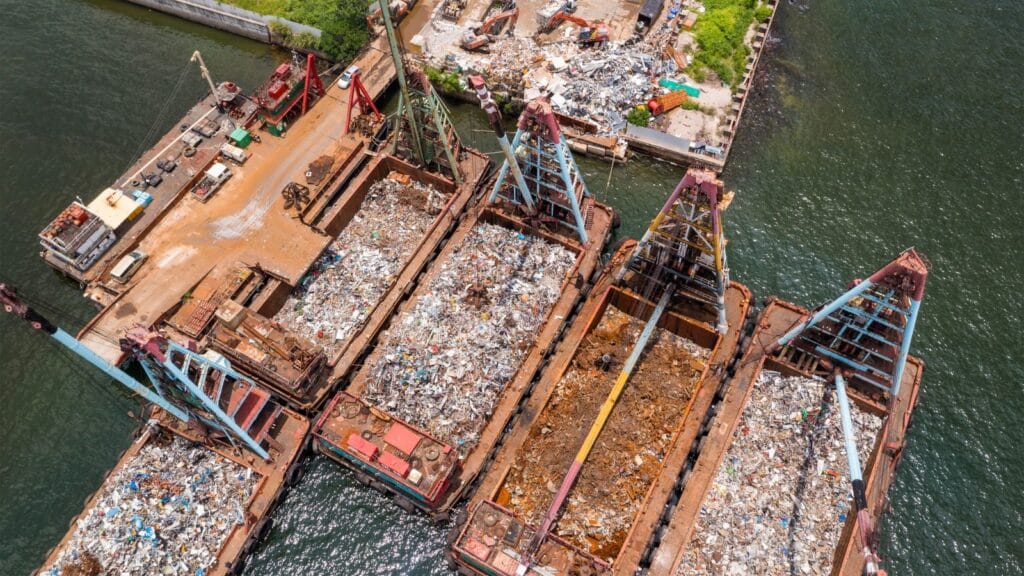

Reality: Much of the exported waste, particularly plastics, ends up in countries with inadequate waste management infrastructure, leading to environmental contamination, illegal dumping, or improper disposal. This practice shifts the environmental burden to poorer regions and undermines true recycling efforts.

Exporting waste to countries with less stringent environmental regulations (which are part of the Basel Convention) and insufficient waste management infrastructure is a common strategy for many companies. It can cause long-lasting damage to both people and the environment. Non-recycled plastic is often incinerated, releasing hazardous chemicals that contaminate communities and the food chain, or dumped into uncontrolled waste sites, leading to polluted water sources and impaired ecosystems. While this practice helps countries maintain a lower carbon footprint on paper, the environmental and ethical consequences are far more severe.

As an example we can set Rome. After the closure of the Malagrotta landfill in 2013, Rome was left without adequate facilities to manage its waste. The city signed an agreement to send its trash to Amsterdam, where it will be incinerated to generate energy for 30,000 households. Although this sounds beneficial and Netherlands is not a country with inadequate waste management infrastructure or laws, transporting waste over such long distances adds significant carbon emissions, reducing the environmental benefits. Fortunately, Rome is working on its own waste-to-energy plant, set to be completed by 2026.

As we can see, developed countries shouldn’t depend on others to manage their waste. The solution is to modernize cities and villages around the country with smart bins and enhance collection routes. Implementing solutions like AI-driven waste collection, sensor-based monitoring, and real-time data analytics can enhance efficiency, reduce costs, and minimize the carbon footprint associated with waste management. By embracing these technologies, countries can also foster green jobs and contribute to a circular economy where materials are reused and repurposed, rather than discarded.

Lie number 4: “Landfills are environmentally safe.”

Claim: Modern landfills are marketed as a safe and effective solution for managing waste and are said to pose minimal risks to human health and the environment.

Reality: While modern landfills do incorporate technologies to reduce environmental harm, they are not entirely risk-free. Leaks can still occur, allowing toxic chemicals to seep into the soil and groundwater, potentially causing long-term environmental damage.

Modern landfills are equipped with various technologies that are promoted as beneficial to the environment and as products to make landfills safer. Here are some of the most famous technologies and their associated problems:

Engineered liner

Although engineered liners are designed to prevent waste leakage, they are not impervious forever. Over time, liners can degrade or develop cracks, allowing leachate (toxic liquid) to migrate into surrounding soil and groundwater. Even minor cracks can lead to significant contamination issues since liners are often buried beneath tons of waste, making repairs impossible once in place.

Liquid collection system

Leachate collection systems can help manage liquid waste, but they are expensive to install and maintain. Additionally, the effectiveness of these systems depends on regular monitoring and maintenance, and even then, they are not foolproof. Over time, pipes can clog, pumps can fail, and leachate can overflow, leading to contamination of nearby water bodies. The cost and complexity of treating leachate further complicate the management process

Daily health and maintenance

While daily measures such as covering the waste can reduce odors and prevent waste from scattering, this process is labor-intensive and costly. Soil or other materials used for daily cover take up valuable landfill space, reducing overall landfill capacity. Alternative covers like tarps are sometimes less effective, and managing pests and odors is an ongoing challenge. Additionally, unexpected weather conditions can exacerbate these issues.

Landfill gas to energy

While gas-to-energy systems capture methane and convert it into energy, the technology is not 100% efficient, and a portion of the methane escapes into the atmosphere. Methane is a potent greenhouse gas, and even small leaks can have a significant environmental impact. Moreover, these systems are costly to install and maintain, and the infrastructure required for energy conversion can face downtime, reducing its effectiveness in capturing methane

As an example of the failure of the technologies listed above, the Bridgeton Landfill fire, which began in 2010, caused significant issues. The landfill struggled primarily with its gas collection system, which failed to properly capture methane and other gasses, leading to harmful emissions. Additionally, the site experienced ongoing problems with the odor from sulfur-based emissions despite the installation of a new system in 2014. Residents continued to report health issues even in 2022. Residents reported ongoing health problems through 2022, and the landfill remained unstable due to the persistent subsurface fire that started over a decade earlier.

New technologies are improving how landfills manage waste, but it is misleading to call them entirely safe or 100% effective. Every landfill, no matter how advanced, still causes some level of environmental harm. The most effective solution is to reduce the amount of waste going to landfills in the first place. By focusing on recycling and composting, we can significantly cut down on landfill usage. Addressing the waste problem before it reaches the landfill is key to minimizing environmental impact.

Lie number 5: “All recyclables are recycled.”

Claim: Once materials are placed in recycling bins, they are all processed and reused, contributing to waste reduction and environmental sustainability.

Reality: Not all recyclables actually get recycled. Many factors influence whether materials are recycled, including contamination, inadequate recycling infrastructure, and market demand for certain materials.

For many, putting recyclables into a bin seems like a problem solved. But what happens afterward? Are these materials truly recycled? Let’s look at common recyclables and the realities behind their recycling:

Plastic:

- Problems: Different types of plastics need to be separated; mixing them reduces the quality of the recycled material. Food residue on plastics can make it non-recyclable.

- Reality: According to National Geographic, 91% of plastic doesn’t actually get recycled. Only 9% has been recycled and the vast majority—79 %—is accumulating in landfills or sloughing off in the natural environment as litter.

Metal:

- Problems: Paint, coatings, or labels on metals can interfere with recycling. Certain metals, such as specific alloys, are difficult to recycle.

- Reality: Recycling rates for metals are generally higher than for plastics. In the U.S., based on a Statista report, lead had a recycling rate of 69% in 2021, with magnesium, aluminum, and nickel all surpassing 50%. Iron and steel had a recycling rate of 44%, amounting to nearly 50 million metric tons of material being recycled.

Glass:

- Problems: Broken glass can contaminate other recyclables, such as paper, and mixing glass colors complicates recycling.

- Reality: In the U.S., about 33% of glass was recycled in 2018, according to EPA data. However, in regions like the European Union, glass recycling rates are much higher. Sweden, for example, consistently achieves a recycling rate of over 95% for glass.

Paper:

- Problems: Food or liquid residue can spoil entire batches of paper, and paper fibers degrade with each recycling cycle, reducing their quality over time.

- Reality: Paper is one of the most recyclable materials. The EPA estimates that about 68% of all paper and cardboard placed in recycling bins is successfully recycled annually.

Overall, it’s clear that a significant portion of recyclables doesn’t actually get recycled. Our responsibility goes beyond just placing items in the correct bins. Reducing waste at the source remains our main goal. Also, with the implementation of modern solutions and improved infrastructure, we can move step by step closer to a future where recyclable materials are 100% recycled.

Sources: changingmarkets.org , eea.europa.eu, european-bioplastics.org, ucusa.org, e360.yale.edu, goodstartpackaging.com, ncbi.nlm.nih.gov, greenmatters.com, recovery-worldwide.com, epa.gov, statista.com, education.nationalgeographic.com, epa.gov, wm.com, simmonsfirm.com, ksdk.com, bbc.com, invw.org, interplasinsights.com

Latest waste library articles

How to recycle cooking oil?

How to recycle?

The role of big data in optimizing industrial waste management

Industrial Waste

How to choose the waste management solution for your business

Smart Waste Management

How to recycle textiles: The vicious circle of waste collection

How to recycle?

Smart Waste Newsletter

Get monthly updates from our company and the world of waste!